The Storythings Attention Pattern Spectrum

Welcome to Attention Matters, a newsletter from Storythings which gives you practical insights and tools to understand your audiences’ attention.

This week we’re sharing a framework that we’ve used in workshops with our clients for many years now. In fact, I’ve just dived through our archive and the first client presentation using this framework was from November 2015. The framework zooms out to show how digital has changed audience attention, which is useful when digital platforms and technologies continue to change at a rapid rate.

We regularly use this framework as part of our audience research and content audits, helping our clients map how they currently reach their target audiences, and where they would like to shift their strategy in the future. If you’d like us to help with your content strategy or production, we’d love to talk.

The Message:

Our attention patterns haven’t just got shorter - they’ve got longer as well

You’ve probably heard it in thousands of meetings in the last few decades - our attention is getting shorter, nobody can concentrate any more, young people have goldfish brains - there are lots of variants on the same message, but they all paint a gloomy picture in which we’ve all been manipulated by our devices to endlessly click, swipe and flit around between screens and platforms.

But all these supposed insights might actually be myths, based on dodgy research and viral statistics, shared by journalists and experts who didn’t give them enough attention (ironically) to check if they were true. In fact, there’s lots of evidence to suggest our attention patterns have stretched out across a much wider spectrum.

The Quote:

“The average amount of time spent watching TV and video content across all devices in 2022 [in the UK] was 4 hours 28 minutes per person per day”

- OFCOM: , 2023 Media Nations Report

The first thing you need to understand about audience attention is that we spend a huge amount of time looking at screens, and especially watching video. This has been the real change that digital has made to our attention patterns - since smartphones put a high quality media device in our pockets in 2007, we’ve just watched more stuff, for more of the day. This reached a peak during the COVID lockdowns in 2020/21, and has come down slightly, but it’s still a lot of time looking at a screen.

The Insight

When you read that we spend 4.5 hours a day watching video, what kind of image do you have in your head? A group of teens, not talking to each other, aimlessly scrolling through TikTok or Instagram?

Well, you’re wrong. The 4.5 hours a day is an average, but the age group contributing most to that is not teens, but over 75s. According to OFCOM, they watch an incredible 6+ hours of video a day, with nearly 5 hours of that being live broadcast TV. In comparison, 16-34 yr olds watch only 3.7 hours a day, and kids from 4-15 only 3.2 hours. And for both these groups, live TV is only a tiny fraction of their viewing, with more of it spread across streaming and social platforms. Obviously not being in school or work gives you time to watch a lot more telly.

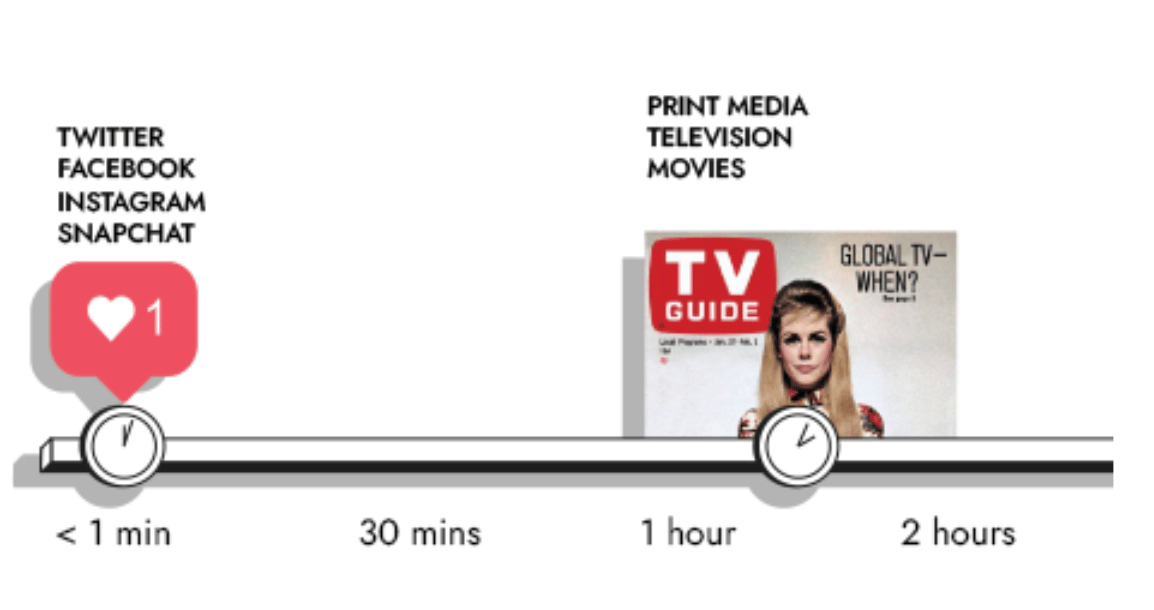

We started developing the Attention Pattern Spectrum at Storythings because we knew the real audience changes from digital were more complex than the belief that our attention patterns were getting shorter. In fact, two things have happened, and to understand them, we need to remember how our attention was managed before digital platforms came along.

If you were creating media in the second half of the 20th century, and wanted to reach a lot of people, you had to work through the dominant distribution mechanisms of the time - print media, broadcast television and radio, or cinema. These media organised their distribution around formats that generally took between 30mins and 2hours of your attention. The TV schedule was organised around 30/60 min blocks (with a few exceptions for live sports and movies), and films were around 90mins because this gave cinema owners the chance to book in two showings a night, doubling their money. If you wanted to tell a story that was 30 secs long, or 6 hours, you would be limited to festivals or art gallery distribution (or ad breaks, but that’s another format altogether).

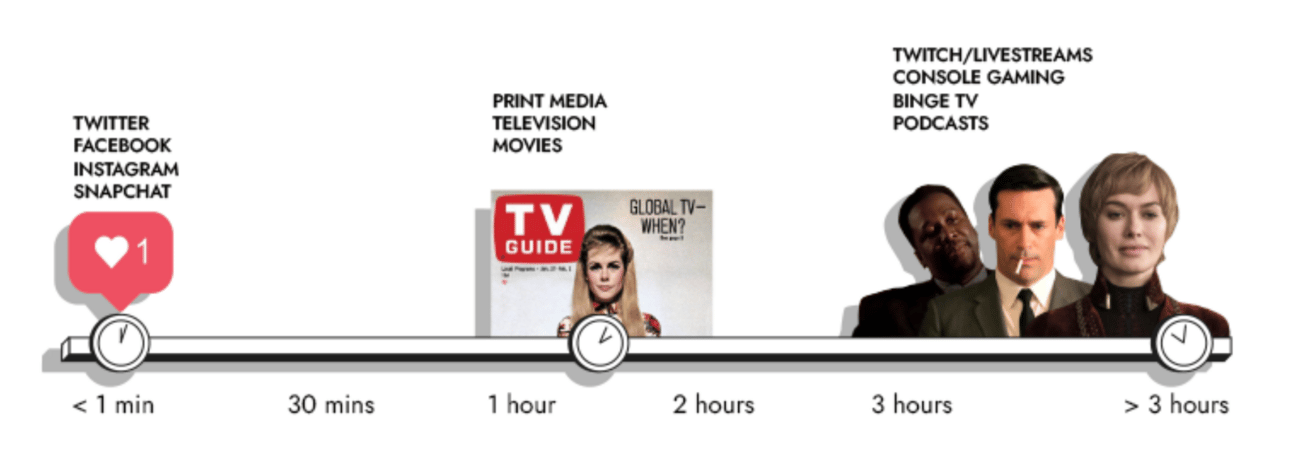

Over the last few decades, digital technologies have done two important things. Firstly, they've created distribution (and monetisation) networks for much shorter attention patterns - everything from a few secs (RIP Vine) to 30 minutes. This is where the social platforms have won our attention (and advertising budgets), and is the change people think about when they talk about attention patterns changing. But it’s not the only story.

The other part of our story is that our attention patterns have got longer - we can decide to immerse ourselves, or ‘binge’ on rich story worlds that we love, whether that is in games, TV serial drama or podcasts.

It was this immersive behaviour that I first noticed when working on digital content for 14-19 year olds at Channel 4 in the late 2000s. Everyone thought we needed to make shorter content for this audience, but when we did audience research, we heard kids tell us they loved spending hours playing online games (World of Warcraft and Runescape at the time, COD or Fifa now). And then the rise of podcasts and Netflix introduced us all to the idea of binge viewing/listening.

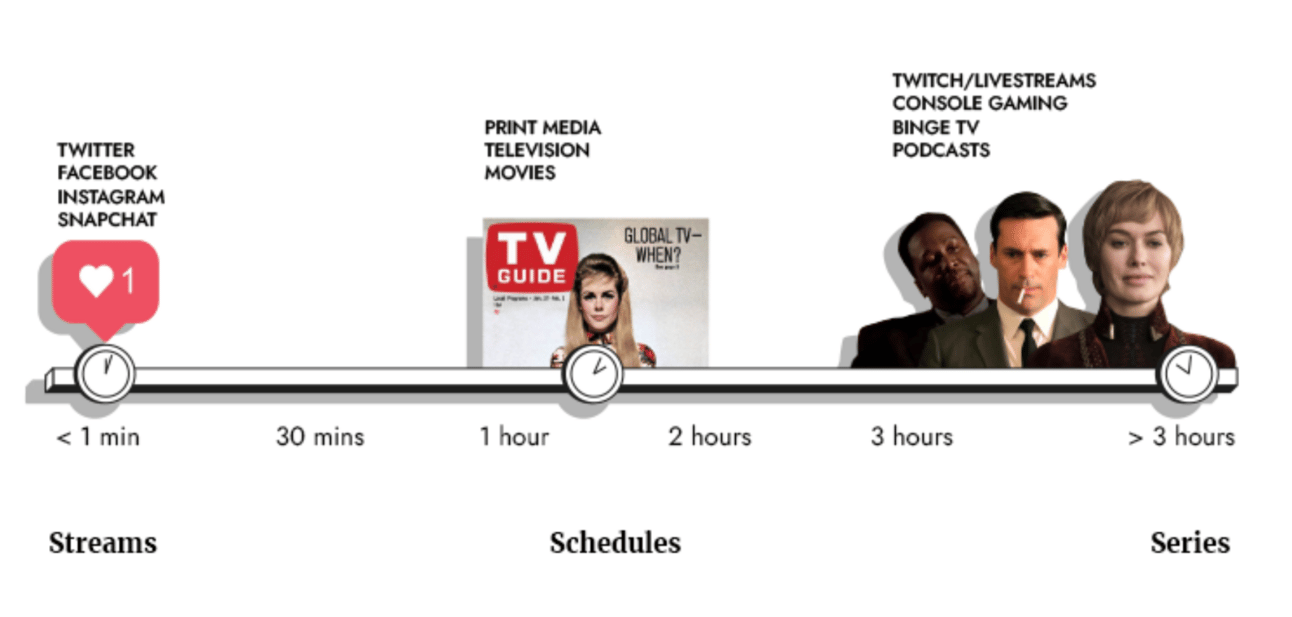

The insight is not that attention patterns are now shorter - it’s that they’re now shorter and longer. We have an expanded spectrum of possible attention patterns that we can create as storytellers, and we need to understand how our audiences fit these different patterns into their lives in order to make our stories effective.

The Action

To help do this, we roughly organise the different lengths of attention patterns into three categories - streams, schedules and series:

Each category has different gatekeepers, different formats, and different ways to measure attention. But we use this framework because it thinks about attention from the audiences’ perspective, not from the perspective of the platforms. We think that the main behavioural changes in audiences have been in response to this broadening of the attention pattern spectrum, and although individual gatekeepers and platforms will come and go, the broad shape of the spectrum will remain constant.

So you first ask yourself - where do we want to reach our audience on this spectrum? How do audiences make decisions about their attention in that part of the spectrum, and who are the gatekeepers who help (or hinder) those decisions? What kind of context and control can you get for your story, what resources or money will you need, and how will you measure your success? And crucially - what is the competition for your audiences’ attention?

Because the Attention Pattern Spectrum is ultimately about one big insight - the growth of mobile digital media platforms has meant we are all now schedulers. We now make thousands of decisions about how we schedule our attention, and even if the platforms are designed to try and take away that agency (by autoplaying the next episode, or presenting us with endless ‘for you’ scrolling streams), we are still way more in control of what we watch, and when, than we were in the age of scheduled media in the late 20th century.

At Storythings, we’ve spent a lot of time researching how audiences are making these decisions, and what we need to do as storytellers to understand the different behaviours and expectations along the Attention Pattern Spectrum, and how we can use these insights to tell more effective stories. If you want us to help your storytelling strategies, we’d love to talk!

Reading list

Alex Mahon, CEO of Channel 4, gave a brilliant Royal Television Society speech last year called ‘Too Much To Watch’ that covered lots of the same issues. We love the research they shared on why people watch video in different ways. Their categories of Relaxing/Passionate/Practical/Time-filling matches our own research, although I think their categorisation of all social streaming platforms as ‘time-filling’ is a bit too negative:

Last year I wrote about why the TV schedule has been so resilient as a way of distributing video and scheduling our attention for us, and why it might, finally, be on the way out.

In 2022, Storythings commissioned Scrollstoppers - a research report into how hybrid working has affected the way we schedule our own attention. There are six insights in the report, including the rise of ‘unscrollable’ media as a reaction to our social streams, and the importance of curators in helping us manage our attention.

If this was worth your attention, we’d love to hear from you! Please reply to this email to get in touch, or share the article on Linkedin tagging Storythings.

See you next time!